I recently started following a poet on Instagram. His name is David Gates, and today he shared verse that stood out. It relates to the question, When do we, as humans, become afraid to ask for help? As Gates points out, we’re not born this way. It’s a learned behavior, and for too many of us, it begins way too early in life.

Have you ever tried imagining yourself as a baby? You were one, once, you know. There are people, “experts,” even, who believe that babies manipulate adults. Some, many considered “good Christians,” honestly think that children are born evil (because of original sin, perhaps?) and that “the devil needs to be beaten out of a child.” Yes, I know, you’re running theological arguments through your mind right now, thinking up ways to push back against this, but that’s not why I made the statement. I am simply stating a fact that has been documented here and there.

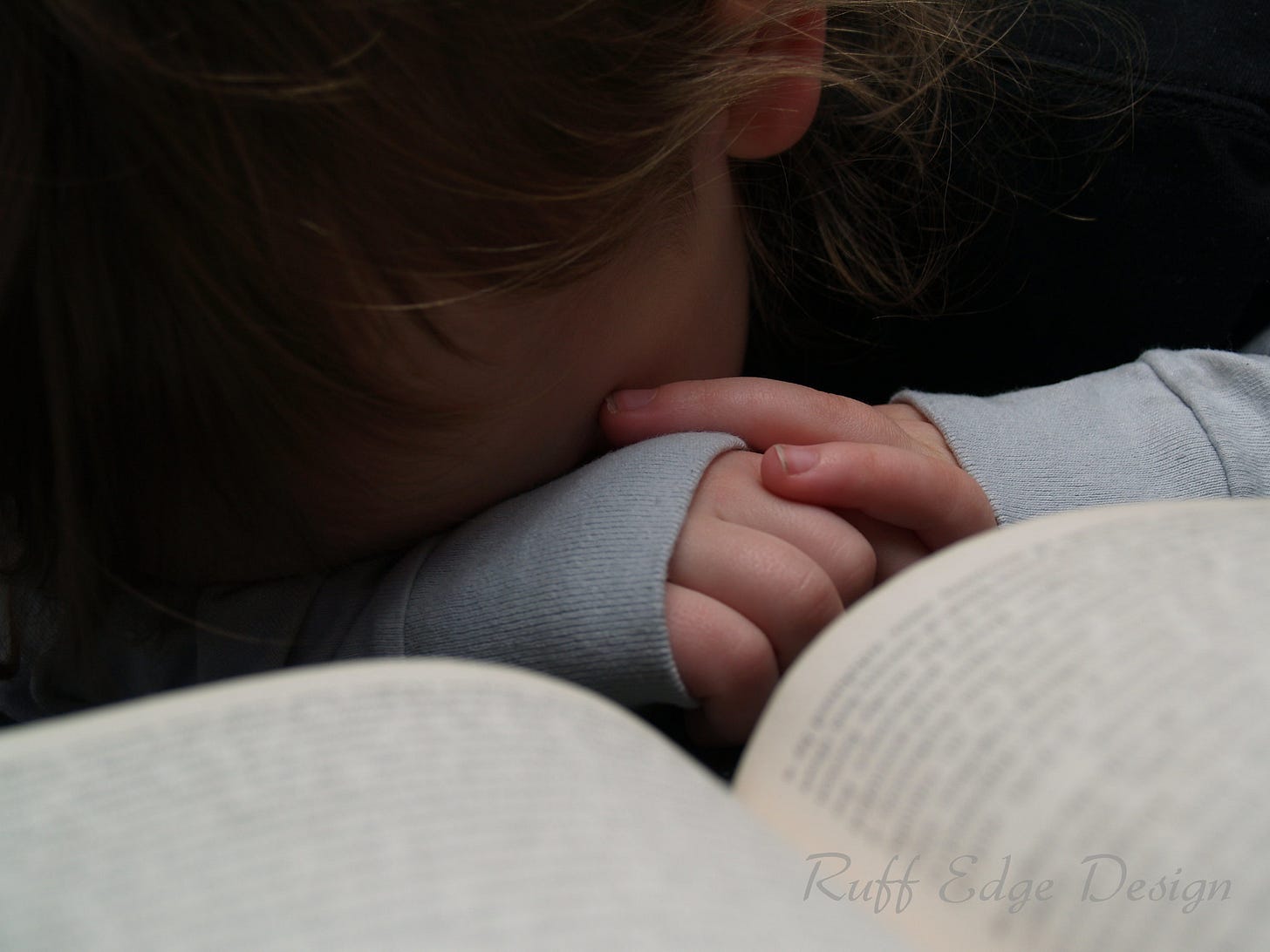

But let’s get back to being a baby again: of what does your universe consist? What do you know? Do you have wants or only needs? If your belly is empty, your diaper is full, you have a gas bubble lodged in your abdomen, or you simply feel like you need to be held, what do you do? You cry, and if your parents, who are your entire universe, are able to see clearly, they attend to your needs as quickly as possible, and when the feeding doesn’t make you happy, or the diaper change does not settle you, or no burp is forthcoming, they continue to try.

I was the youngest of three children and had maybe ten hours of experience in caring for babies (through limited stints as a babysitter) when I gave birth, at age 26, to my son Luke. For four months (until I introduced a few foods like rice cereal), I managed—with the help of my husband, when he was not at work or traveling (as he did two or three times a month), and my sister, when she was available—to not only keep the boy alive, but to breastfeed him exclusively and on demand, to respond to his every cry and need, and to do it as best I could, given the pain, the lack of sleep, the lack of understanding from others, the panic attacks, and the postpartum depression (never identified) that had me fearing I’d go crazy and drop him over the railing of the loft in our 700-squre-foot, two-story condominium.

We had a crib, but each night, Luke slept between Dennis and me, where my sleep cycle got in sync with his, so I could wake from a light sleep when he woke and nurse him lying down.

I give myself credit for doing the right things with no previous experience and not enough support. I am incredibly thankful that, before we were married, Dennis and I took natural family planning classes from The Couple to Couple League and learned about extended breastfeeding and its challenges, co-sleeping, and attachment parenting. Did I get everything right? Not even close, and if I could go back and change things I would, including what could have turned into an enormous mistake:

When I brought Luke in for his six-month checkup, the pediatrician asked if he was sleeping through the night yet. I now know that a baby’s ability to sleep through the night is nobody’s business, but back then, I thought that this doctor, who saw my child for ten minutes every few months, knew more about him than I did. So, I took her advice that night, and put Luke down in his crib after nursing him to sleep. He immediately woke (as I knew he would) and cried. I put my hand on his belly, said some “comforting” phrases, and walked away. I went back, touched him, and said the phrases, every ten minutes or so, for the 45 minutes it took for him to become so bereft and exhausted that he finally fell asleep. Those were some of the most excruciating 45 minutes of my life, and I swore that I would never do that to him or any other child ever again, and I didn’t, if I could help it (car rides when I had no one else to drive were another story).

So, if, as David Gates points out, we are born telling the truth about our needs, how and when do we learn to shut up? Is it when we are “sleep trained” to understand that our parents do not love us enough to come to our rescue? Is it when we are simply being children, saying and doing whatever comes into our heads, because we are children, and are suddenly reprimanded, yelled at, scolded, slapped, or spanked and for the life of us, we cannot understand what we could possibly have done to make this person we are dependent upon for our very survival stop loving us and hurt us, instead?

I left a comment on David’s poem, asking if he had read anything by Alice Miller (because he seemed to just about get it). He replied in the negative, and I shared the following with him:

Her books changed my life. Essentially, her theory, which is rejected in one way or another by the mainstream mental health biz, is that "poisonous pedagogy," the socially accepted ways most of us are parented, affect us throughout life, unless we are able to look back at what we experienced and express the emotions we were never allowed to as children. Our bodies react to every experience with emotions, and these are not the same as intellectual knowing. In my case, I know intellectually (as an adult) that my parents loved me, but as a child, I believed that their love depended upon whether or not I behaved myself, got good grades, "succeeded" in life. I had no idea that this was the case, until Miller's writing struck a chord, and my need to achieve, to please others to the extent that I didn't know who I was, all flowed from this belief. Your poem talks about hiding the helplessness. That's what I had to do, because being anything but calm, obedient, and "happy" upset my mother. Interestingly, I got clues about all this through my own poems, essays, and art, and I found myself rebelling against things that had a hold on me, but I didn't know why. Miller died in 2010, but her website has a lot to offer: http://www.alice-miller.com/en/

I understand perfectly why most of you who have read my recent posts have never once reached out and asked about what I’ve shared. I hope this post helps you understand why you’ve not done that.

"Have you ever tried imagining yourself as a baby?" is the perspective that helped me break through to understand what you and Alice were trying to say. From that point of innocence springs confusion and then, very quickly, the conscious and unconscious lessons about what to expect and not to expect; how things "are done" and "are not done."

This perspective, this thought exercise, helps one look at much that we thought we knew with a humble "oh." The lesson here is simple, but has profound and scary implications that one encounter in each encounter, and that cause one to re-process what one thought they understood in life, art, scripture, philosophy.

That is heavy lifting.